Colorado Springs Community Cookbook

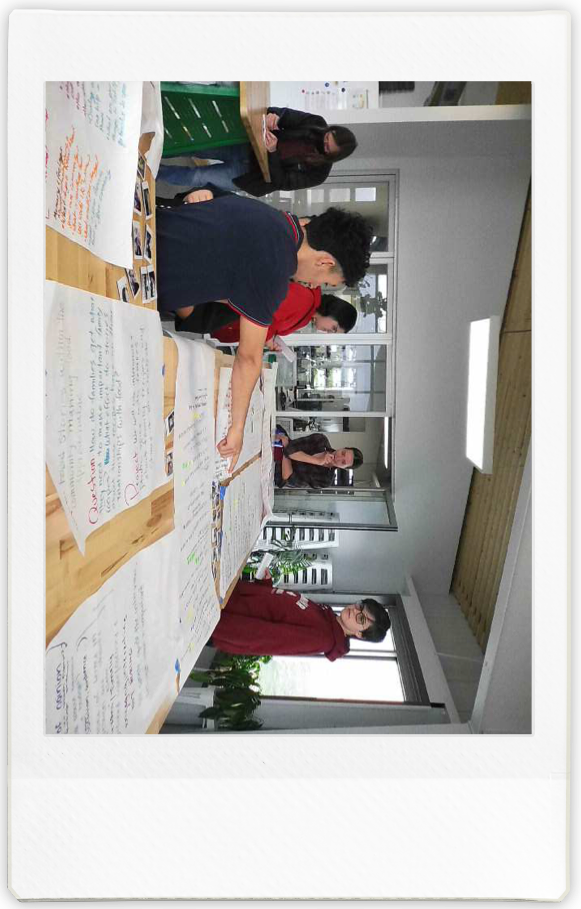

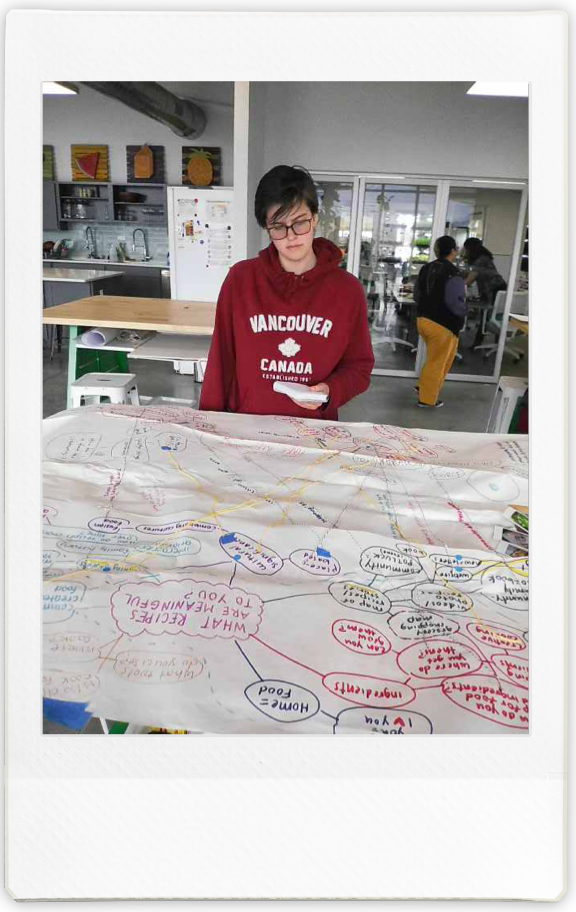

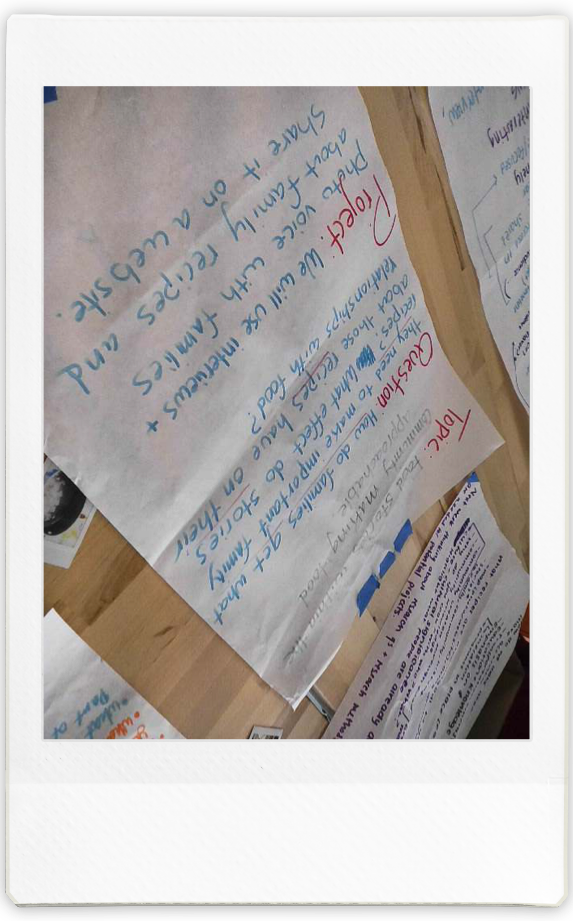

From October 2022 to May 2023, a group of paid youth researchers came together to better understand food access, food justice, and culinary justice in their community. Informed by critical pedagogies, Participatory Action Research, and the food justice movement, adult facilitators developed a curriculum that prompted youth researchers to identify a food-related issue in their community to investigate for the duration of the program. PARTY youth drove the topic and agenda, posed research questions, selected their methods, and completed the project with adult assistance and facilitation. As a result, the PARTY youth developed a project that allowed them to highlight community knowledge and celebrate their families.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In other words: “on

Tuesdays there's this place where, basically, they give a new fresh meal every

day, you share your ideas with people, and you get paid for it!”

- Sal, Youth Researcher

- Sal, Youth Researcher

You can view the final cookbook here.

Review our Research Questions, Methods, Findings, Implications, and Lessons Learned by scrolling below. ↓

Research Questions

How do families get what they need to make important family recipes?

How do stories about those recipes shape families' relationship to food, community, and culture?

Methods

In order to address the research questions, we conducted audio-recorded in-depth interviews, photos, and observations with families in the Food to Power community as they cooked their important family recipes.

We recruited informants through tabling at Food to Power’s no-cost grocery program, and asking our own families and friends to participate.

“When

Food to Power would do its [no-cost grocery program] we would get into pairs

and then we would ask the people that came here if they would be interested in

participating in the study. And we told them what it was going to be about. We

told them what the requirements were, simple questions to see if they're able

to participate in the study. And then once like we did that, we scheduled

everybody and then we started interviewing people.”

- Leslie, Youth Researcher

- Leslie, Youth Researcher

We conducted interviews with 19 families (53 total informants). Five interviews were conducted in informants’ homes, the remaining 14 were conducted at the Food to Power Hillside Hub kitchen.

In interviews, we asked informants questions about culture, memories, and stories related to their dish; the history of their dish; what makes their dish special; the dish’s impact on their lives; and challenges to preparing their dish.

“Most

of the interviews were just here [at Food to Power], so usually they'd just come to the door with

all the groceries and everything. We'd greet each other and then you

know, they'd lay out all of the things and then we'd have a recording

going of the interview. Well, and then I would just, like, if I'm one

interviewing, I'd start going through some of the questions and then of course

they'd answer and I'd kind of just try to keep a natural conversation going for

as long as possible.”

- Sal, Youth Researcher

“It wasn't exactly a standard interview where you just sit down with either one person or a group of people and you just ask them questions individually or as a group. We had it where one person or multiple people would be actively making their recipe and their dish. And as they went along, we would ask them questions and take pictures to try to capture as much as possible.”

- Dylan, Youth Researcher

- Sal, Youth Researcher

“It wasn't exactly a standard interview where you just sit down with either one person or a group of people and you just ask them questions individually or as a group. We had it where one person or multiple people would be actively making their recipe and their dish. And as they went along, we would ask them questions and take pictures to try to capture as much as possible.”

- Dylan, Youth Researcher

Preliminary Findings

After conducting all the interviews, we looked at our notes, photos, and excerpts from written transcripts of the audio-recorded interviews to reflect on themes related to our research questions. We worked independently, then shared our ideas with each other as a group. Below are some of the preliminary themes we found:

Strengthening Family Ties:

Teaching, cooking, and eating these dishes were a conduit for sharing family histories and connecting as a family. Valerie makes a cucumber salad recipe with ingredients her grandparents made and grew as farmers in Nebraska. Ryan cooks Irish dishes to feel connected to his extended family in Ireland, who he doesn’t often get to see, and to bring his partner into his Irish culture. Viane’s sisters and cousins cook Tanzanian sambusas together; shaping, filling, and frying 60 individual sambusas can be a joyous activity when many cousins gather around a table to do it.

Most families did not have a written recipe for their dish, and cooking required getting together or making phone calls to get it right. For example, Janvier called his sisters and nieces to teach him how to make Congolese food over the phone when he moved to the U.S. Thomas called his dad to get the instructions for his Grandma Lupe’s soup until he got it right.

Frequently, families gathered to cook a recipe that honored a specific person, sometimes someone who passed, is far away, or is otherwise challenging to connect to. For example, Natalia’s tía Josephine, who always cared for everyone in the family, has dementia and does not cook her classic dishes any more. Natalia’s family makes her tía’s ceviche recipe because “a world without my tía’s cooking doesn’t make sense.”

Seeking Independence:

Learning to cook and teaching family members to cook was tied to independence. Many informants learned to cook from a family member as a child and have passed on that skill. For example, Graciela's mom taught her to make tamales as a child, and Graciela brought that knowledge with her when she moved to the U.S. from Mexico. Like her mother, she sometimes sells tamales at festivals and other special occasions. Jeannette learned to cook from her grandmother and ensured her kids started cooking at about ten years old or younger. Now that some of them are out of the house, she is proud they know how to cook and care for themselves. Diana learned to cook at about ten when her mom taught her to make roti. After that, she frequently made meals for her many siblings growing up back home in Trinidad. Natalia’s mom and aunt encouraged her to learn to cook so she would not have to depend on anyone, and she wanted to pass these skills down to her young daughter.

Gathering Ingredients:

Many dishes were initially created out of ingredients that were accessible, available, and affordable. For example, Thomas’ grandma Lupe created her Beef Soup from extra hamburger meat her husband brought home from his job at a meat packing plant. Janvier’s fufu recipe is typically made of cassava flour, a staple in his home country of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sarah’s cake was adapted from traditional recipes to use more commonly available ingredients during the Great Depression.

The availability of ingredients today in Colorado Springs varies considerably. Some people visit many stores and pantries to get their desired ingredients. Others had an easier time getting everything they needed in one place. Ingredients for international dishes took much work to find. For example, Jeanette went to several Walmarts, each progressively further south in Colorado Springs, to get Goya empanada dough. In contrast, families seeking ingredients considered "American" had an easier time finding them.

Implications

Why are family recipes important? How does food access and food security connect to family stories about food?

“[Culinary justice] is not only

having food to eat, but the foods that you want to eat or that are important to

you because that really helps people's relationships with food…because it could

be really emotional for somebody. I know I have certain foods that I feel

really connected to my family when I make them. It's having an option. It's not

just, “this is what you get,” it's having an option of what you want to eat.”

- Calah, Youth Researcher

“Culinary justice is making sure that people, all people, have equal access to the resources that they need concerning food. And that it's not just to food that they need to eat in order to survive, but also food that they can access that will help them make foods that they remember, like their childhood or culturally significant food if they're not living in the same area or country that they used to be living in.”

- Dylan, Youth Researcher

- Calah, Youth Researcher

“Culinary justice is making sure that people, all people, have equal access to the resources that they need concerning food. And that it's not just to food that they need to eat in order to survive, but also food that they can access that will help them make foods that they remember, like their childhood or culturally significant food if they're not living in the same area or country that they used to be living in.”

- Dylan, Youth Researcher

What We Learned

Research Skills:

“First,

we learned about different methods. We learned about the general basics of a

research question and themes and we started off by naming ideas or things that

stemmed off of food. And then we figured out what can we research more on

what's needed to be researched more on or we tried looking for problems and

then we made sure it was relevant, relevant to our community and to the program.

And then from there we either got more ideas from what we've got, or we learned

more about other things and then we came back to it and we switched stuff

before, like choosing our final project to work on.”

- Leslie, Youth Researcher

- Leslie, Youth Researcher

Carrying Out a Long-term Project:

“My favorite

part about doing this project was behind the scenes, understanding what it

takes to develop an idea and what it takes to execute an idea to what it takes

to actually do it in person the first week and then continuously do it until

the finished product comes out. Whether, if it comes out bad, whether we

improvise to make it look good. I really like that process.”

- Jose, Youth Researcher

- Jose, Youth Researcher

Community Engagement:

“I think [working on this project] made me feel more in

tune to…the Food to power community because I actually hear from the people

that come here and I hear their voices. But it's also made me inspired to

engage more with the other communities that I'm part of, like the Palmer [High

School] community and help if there's like a specific issue, like help make

other people's voices heard or listen to other people when it comes to those

specific issues…I think being a part of this has helped with my listening

skills a little bit.”

- Dylan, Youth Researcher

- Dylan, Youth Researcher